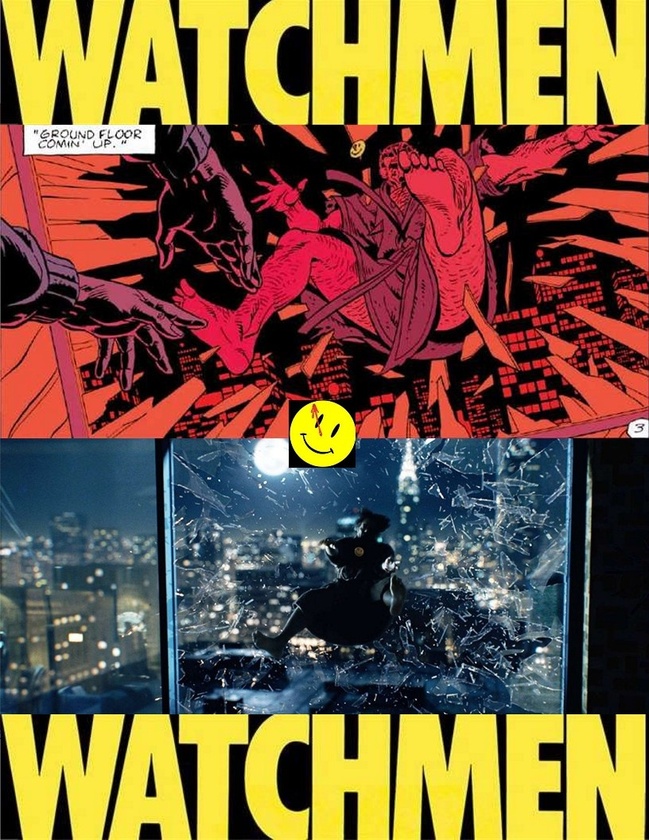

We are all introduced to comics at some point in our lives. (Who hasn’t read a Peanuts comic strip?) Sadly, the comic book, or graphic novel (collection of comic books), is looked down as a children’s pastime or ruled out as non-compelling literature altogether. On March 6, 2009, the highly anticipated film adaptation of the first graphic novel to be praised as a master work of literature made its big screen debut.

There is no immediate consensus on public reaction to the film. Depending on which group you fall under, you would either love it for its originality, or hate it for changing pivotal scenes from the source material after constant promises to stick as true to the book as possible.

This article appeals to both the educated and uneducated persons in the world of the WATCHMEN!

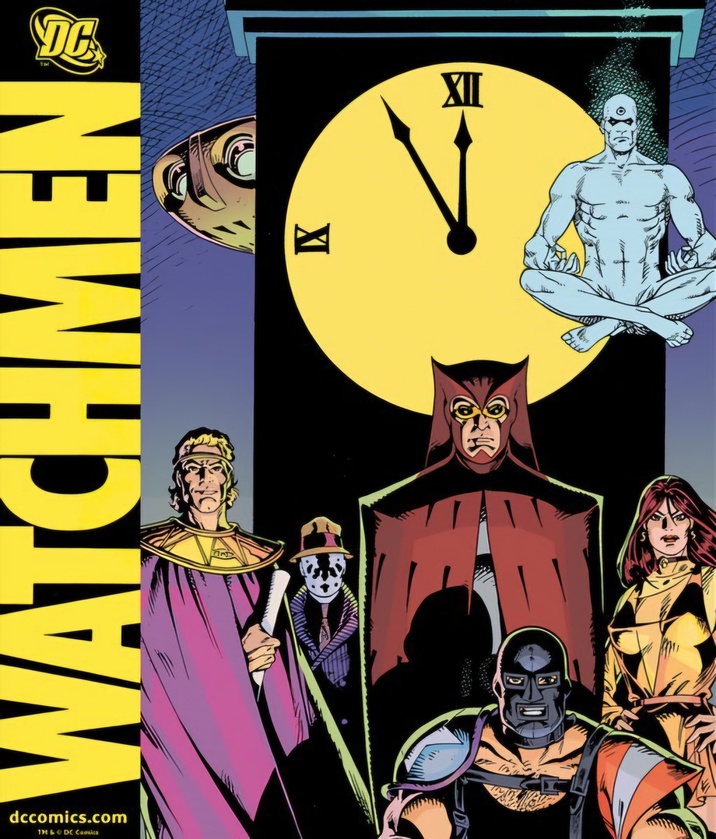

THE NOVEL

Before I can begin, you need to know the story of the Watchmen (assuming you haven’t seen the movie by this article date).

This synopsis from the publisher DC Comics:

“It all begins with the paranoid delusions of a half-insane hero called Rorschach. But is Rorschach really insane or has he in fact uncovered a plot to murder superheroes and, even worse, millions of innocent civilians? On the run from the law, Rorschach reunites with his former teammates in a desperate attempt to save the world and their lives, but what they uncover will shock them to their very core and change the face of the planet! Following two generations of masked superheroes from the close of World War II to the icy shadow of the Cold War comes this groundbreaking comic story — the story of The Watchmen.”

None of the heroes from the novel are recognized instantly in our culture. None of the heroes ever got spinoff comics after the critical acclaim of the short series. Watchmen is a murder mystery developed with the same hard work and care that goes into making a fiction novel. Both author Alan Moore – famous for this and other works of fiction such as From Hell and V for Vendetta – and illustrator Dave Gibbons have painfully crafted a complex, multilayered, psychological anti-hero adventure that spanned a year in telling (1986-87). The end result is the perennial and most influential “graphic novel” ever accomplished. The humanity exuded by each character is strikingly real and relatable. It is this main element along with the real-world scenario that inspired realistic retellings of future popular comic book superheroes.

The story takes place in an alternate United States in 1985. The world is in the middle of a Cold War, particularly between the two nuclear superpowers: the USA and the Soviet Union. The setting nearly parallels our world except that masked vigilantes are part of the culture, the USA wins the Vietnam War, Richard Nixon is still President in 1985 and the “Superman does exist, and he is American.”

The attention to detail in terms of the character development, political climate, public sentiment towards masked heroes, and government employment of heroes is all very real, very relatable, very, um, heartfelt. It’s the realism of the plot that turns the story from a mere fiction to a piece of American History.

For those that haven’t noticed, up until the debut of Watchmen, the only heroes mingling with citizens of real-world cities belonged to Marvel Comics. DC Comics superheroes live in alternate versions of American cities. (e.g. the equivalent of New York City and Chicago in the DC Universe are Metropolis and Gotham City.) Along comes Watchmen and thrusts heroes not only into our cities but into our cultural history. It is this connection to the real world, the very real interaction between masked heroes, the average citizen, federal government, etc. that sets Watchmen on a league of its own. Many have tired duplicating it but have never matched its complexity and success.

It is safe to say that the medium of comic books has never been the same since. And with many popular comic books getting motion picture adaptations, the movie treatment for Watchmen was unavoidable. It was just a matter of when a good script, the director with the right approach and visual style to bring the story to life would come along. Twenty-three years later and after a surge of an ever-increasing number of comic books-turned-films hitting multiplexes, Watchmen finally made it to the big leagues with a nearly 3-hour epic theatrical release.

THE FILM

The Watchmen movie version moved around different studios with scripts written then rewritten over and over again without any true convincing concept to bring to the big screen. Director Terry Gilliam used to be tied to directing the big screen adaptation in the late 90s. He stated best the complications of making a 2 ½ hour version of the novel:

“Reducing [the novel] to a two or two-and-a-half-hour film … seemed to me to take away the essence of what Watchmen is about.”

I, like Terry, agree that a miniseries would’ve been the best avenue with which to approach the story. Though it felt like an eternity, it was inevitable that the graphic novel would get its major motion picture treatment. Now is a good-a-time as any to do so since movies containing dark, mature subject matter are drawing more audiences to the theatres (e.g. The Dark Knight).

The difficulty in bringing about this book-to-screen adaptation is in how to keep the essence of the book intact while making the film a fascinating viewing experience. Compromises had to be made, of course. Whenever anyone is tackling the adaptation of a popular work, groups of purists, fans, and dissenters will always be nearby ready to level any criticism in attempts to impact the filmmaking process.

The great risk of Watchmen is that it is not really adaptable without first tossing out important elements of the book that make the story “the story,” and still keep it short enough to screen at a theatre near you. Warner Bros realized this issue which is why they hired Director Zack Snyder to take the helm for the project. They needed to stay as true to the source material as possible. Zack Snyder promised to deliver the goods as he did with Frank Miller’s 300.

Ultimately, an all-important comic-within-the-comic – Tales of the Black Freighter – didn’t make the final cut, but it is getting its own film treatment as a direct-to-video. However, the comic tale is such an integral part of the major story that Warner Bros is producing a special DVD release that will include deleted scenes and the Tales of the Black Freighter edited into the main film.

This is evidence that the filmmakers knew the importance of keeping integral parts of the novel in place and did their best to execute the film appropriately. Comic book illustrator Dave Gibbons was brought on early on to supervise the filmmaking process to make sure they stayed true to the source.

THE CONTROVERSIAL ENDING

A fan could sleep soundly knowing that such a talented team dedicated to preserving the essence of the novel is developing the movie, right? Well, months before the initial release date, speculation about a major revamp to the climax grew amid attempts to keep it hush-hush. After constant pressure from the press and fans director Zack Snyder dropped the bombshell confirmation that the most major element and integral part of the script was altered to suit a more general audience.

The squid in the novel is a byproduct of artistic design and genetic engineering developed under the guise of a movie special effect. The actual purpose of the disgusting, giant squid was to fool the world into thinking it’s an alien from another dimension hell-bent on destroying all humanity.

The movie version of “the squid" is re-imagined as a supposed new energy research project intended to provide cleaner, more efficient means of energy to an ever-growing human population.

The actual purpose is for the villain to reengineer these large mechanical devices, use them as psychic energy explosives each with the destructive power of an A-bomb, and frame one of the Watchmen for the attack.

The villain’s end game in both mediums is the same: unite the world by scaring them into believing they must ward off a common enemy. In both cases he succeeds

The Original Ending

When Rorschach investigates the murder of Edward Blake – alias The Comedian – he believes there is a plot to kill off costumed heroes. He sets off to warn other retired heroes of his findings. While Rorschach is investigating the murder there is an entire other mystery being covered by the Press: the mysterious disappearance of yet another famous creative artist. The artist is among a group of his peers that “vanishes” without a trace. He is working with scientists, engineers, and others on a secret project for an unknown “filmmaker” all along. Rorschach’s wild theory about a mask killer is taken more seriously when another hero – Adrian Veidt – is gunned for, Dr. Manhattan flees the earth for Mars, and Rorschach is framed and imprisoned. All this is occurring during a time of political tension between the two superpowers threatening to go to nuclear war and lay waste to the earth.

Illustrator Dave Gibbons was asked about the cutting of the squid during a Q&A session at the 4th Annual New York Comic Convention back in February. His initial response was:

“The outcome is exactly the same as the graphic novel, but the MacGuffin, the gimmick, is a little different. I think you know what I mean; there's no squid. I'd rather not say too much about it, but I certainly wasn't at all upset or disappointed or offended. I think that's the most important thing about the movie adaptation is that it has to stand as a good movie. The reality of it is that you have to make changes and you have to take things away, add things on, amalgamate things to make it work in a different medium."

After a follow-up question regarding the squid, he answered:

“Why is the squid so important? In a sense, in the comic book, the squid is kind of a huge special effect that Adrian Veidt pulls, a practical joke, a trick, but if you have a movie that essentially is full of special effects, then the squid is just another special effect, if you see what I mean, so that I think that wouldn't have worked as well in the movie. That's my personal feeling about it. Sorry for all your cephalopod lovers out there.”

So, Dave isn't really a fan of the squid since he wasn’t disappointed by its omission from the film. He didn't write it. He drew it from concept ideas by author Alan Moore. For Dave to come across with little regard for the original concept comes to show that even he doesn't understand what exactly Moore accomplished with the alien squid.

Historically, anyone believing aliens exist is thought of as kind of crazy. Whether there's evidence to support the existence of aliens isn't the issue here. Imagine the disbelief at seeing a horrific scene such as a monstrous, alien squid appearing in the middle of Manhattan and killing millions an in instant. The apparent “attack” by an alien being would more likely unite a world of differences against a common enemy.

The idea of forging alliances amid a foreign invasion isn't farfetched. It’s happened before. When the Japanese invaded China, the Chinese Communists and Nationalists united albeit under a temporary truce to ward off the Japanese. After the horrific events of September 11, 2001, America put aside its ideological differences albeit for a while to seek justice against a common enemy.

The Alternate Ending

The framing of Dr. Manhattan in the movie adaptation doesn’t make any sense unless you’re on the left side of the political spectrum. See, the subliminal message I drew from the altered ending is that Dr. Manhattan is viewed as a walking A-bomb created and used by the United States government for the “greater good.” When the psychic charges are detonated on major cities across the world, the world suddenly forgets about nuclear war and unites to defend itself against Dr. Manhattan; man’s own god-like power turns against man. The film concludes with the world adopting clean energy alternatives and world peace.

That’s it.

Well, why would Dr. Manhattan attack the world in the first place? He was framed for giving his former loved ones cancer, felt terrible believing he was guilty of it, leaves the Earth for Mars, then returns to kill millions around the world? Nonsense. Also, the USA didn’t create Dr. Manhattan; he was an accident. This only scratches the surface of why the ending doesn’t make sense. You’d have to read the novel to understand The Comedian’s emotional breakdown, his murder, and the shock value of what ultimately convinced the USA and USSR to make peace.

WHICH IS THE BETTER ENDING?

The debate continues. The novel’s ending always sparked debate about whether it was a great or lackluster ending to a great novel. The movie ending caused a stir prior to the film’s debut quickly causing an outcry from purists and debates among the viewing public.

Yes, the outcome of the film's and novel's ending is the same, but the point missed here is that the means to that end are what intrigued the reader in the first place. So many mysterious occurrences having seemingly nothing in common throughout the plot actually are tied at the end of the novel through the monstrosity of the squid.

CLOSING COMMENTS

At least the film’s lead up to the poorly constructed ending was very well done but could have been better without slow-motion.

Still, the ending should’ve remained intact instead of trying to appeal to a more general audience. Fanboys are always a major draw at the box office (e.g. The Dark Knight). The movie opened well below expectations and doesn’t seem likely to recoup its budget in the domestic market.

The book will always be superior to the film.

–Andres Segovia

Published 3/11/2009

Revised 7/1/2024